What the new Iran-China partnership means for the region

Published on: 2020-08-07

This new realignment in Asia provides new opportunities not only for China and Iran, but also for Pakistan.

By Abdul Basit – 6th August 2020

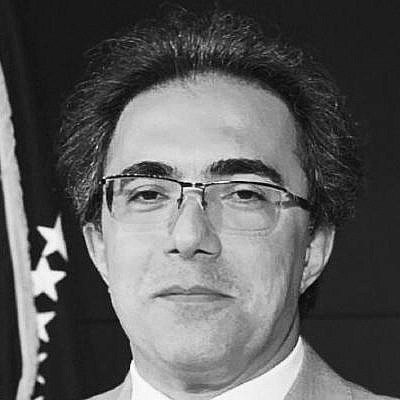

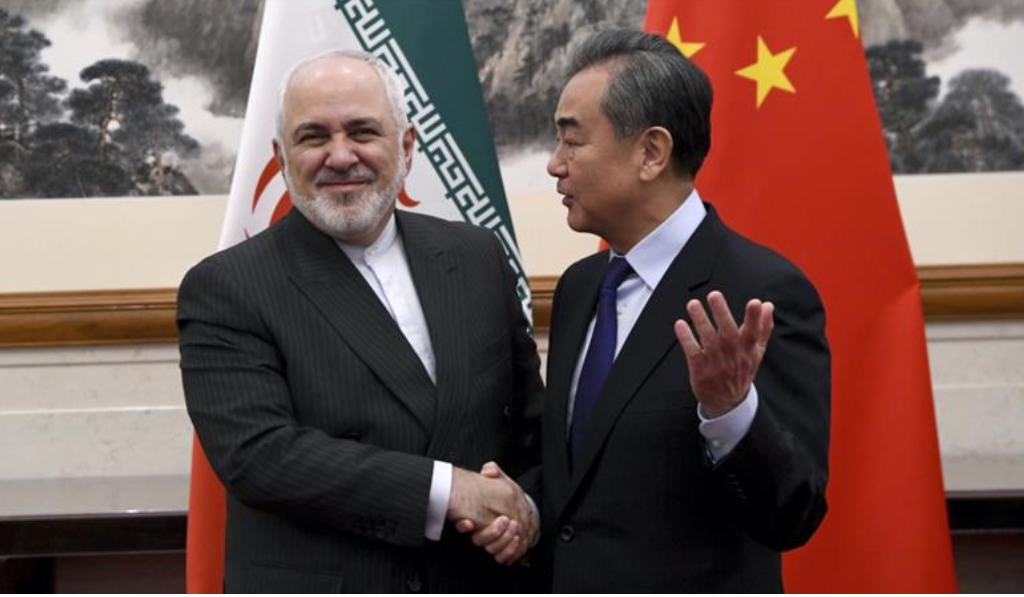

In early July, Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif announced that Tehran is close to entering into a long-term strategic partnership agreement with Beijing. A few weeks later, Indian media reported that Tehran has “dropped New Delhi” from a key rail project along its border with Afghanistan after “it showed reluctance in investing fearing American sanctions”.

Despite occupying headlines around the same time, the news of Iran’s newly formed strategic alliance with China and its alleged cold-shouldering of India were not directly related. Nevertheless, viewed together in the context of the growing tensions between the US and China and the Himalayan border dispute between China and India, these two developments provide valuable insights into the new geopolitical realignments in Asia. It seems the Trump administration’s “maximum pressure” policy against Iran has pushed the country into the arms of China and caused a significant strategic disadvantage to its long-term ally India.

According to a July 11 report by the New York Times, the not yet finalised agreement between Beijing and Tehran will see China invest a total of $400bn in banking, transport and development sectors in Iran. In exchange, Beijing expects to receive a regular, and heavily discounted, supply of Iranian oil over the next 25 years. The deal is part of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s ambitious Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that aims to extend his country’s economic and strategic influence across Eurasia.

Just a few days after the details of the proposed China-Iran deal were made public, on July 14, Indian daily The Hindu reported that Iran decided to exclude India from an extensive rail project that will connect the Iranian port city of Chabahar to Zahedan, a city near its border with Afghanistan. Indian consultancy IRCON had pledged to provide all services and funding for the project, estimated at about $1.6bn, according to The Hindu report.

The Iranian government swiftly denied the Indian newspaper’s report, claiming it did not drop New Delhi from the project, as it had “not inked any deal with India regarding the Zahedan-Chabahar railway” in the first place.

Despite Tehran’s denial, however, many viewed India’s apparent removal from the railway project – which will eventually stretch to Zaranj on the Afghan side of the border – as a major setback to its plans to create an alternative trade route to Afghanistan and Central Asia that bypasses Pakistan’s Chinese-operated Gwadar port.

Chabahar is pivotal to the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), a 7,200-kilometre (4,473-mile) freight route connecting Mumbai to Moscow. For years, India had been enthusiastically promoting the project, which aims to increase connectivity in Eurasia, partially because it believed it could help keep Iran outside China’s BRI, and cool down any cooperation attempts between Tehran and its primary regional rival, Islamabad.

Over the past 20 years, Iran had been supportive of India’s plans to establish new trade routes and signed several deals to advance these initiatives. Last year, however, as New Delhi stopped purchasing oil from Iran to please Washington and further strengthened its military-strategic ties with its arch foe, Israel, Tehran’s attitude towards New Delhi’s regional connectivity project started to change. The news of New Delhi’s interest in participating in the Israeli-led “Trans-Arabian Corridor” (TAP), which aims to connect India to Eurasia through Israel and several Arab states hostile to Iran, further encouraged Tehran to seek other regional alliances.

Iran’s new partnership deal with China is indicative of its drift away from India. And this budding partnership between the two countries is likely to have significant consequences for New Delhi.

The new deal between Beijing and Tehran includes plans for China to develop several ports in Iran, such as the Bandar-e-Jask port which is strategically situated to the east of the Strait of Hormoz. This is significant as it gives Beijing control over one of the seven key maritime chokepoints in the world. This can potentially undermine the US naval dominance in the Middle East, as having a foothold in Bandar-e-Jask would not only allow China to monitor the US Navy’s Fifth Fleet based in Bahrain, but together with a presence in Gwadar and Djibouti ports, it would also augment Chinese presence in the Indian Ocean Region. All this could cause India to lose the leverage its close ties to the US provides against China.

Iran’s inclusion into the BRI framework is also likely to cause India to lose ground against China in Afghanistan. After 9/11, Indian political and economic influence grew in Afghanistan under the US security umbrella. Since the February deal between the US and the Taliban in Doha, however, India’s influence over the country has been shrinking. India was neither part of the US-Taliban deal, nor it has any significant role in the intra-Afghan peace process. After the US withdrawal, India’s influence over the country will minimise further.

Despite Washington’s prodding, New Delhi has been ambivalent about entering into dialogue with the Taliban. China, on the other hand, has long been engaging both with the Kabul government and the Taliban in an effort to not only secure its economic investments and interests in Afghanistan in the aftermath of US withdrawal, but also undercut those of India. This also gives China an edge to potentially connect the post-US Afghanistan in the BRI framework. China’s growing ties to Iran – a country that has significant clout over and ties with Afghanistan – is likely to help it achieve this goal.

This new realignment in Asia provides new opportunities not only for China, but also for Pakistan. First, China’s involvement in Iran would weaken Pakistan’s main rival India, and open up strategic space for Islamabad to efficiently deal with political and security threats it is currently facing. Second, after fully integrating Iran into the BRI framework, Beijing could help Islamabad improve its relations with Tehran and assist the two countries in pacifying the ethno-separatist armed uprising in Balochistan. Third, Chinese presence in Iran would mean the Iranian port city of Chabahar would not compete with Pakistan’s Gwadar, whose port is operated by China. Finally, India’s ouster from Iran would mean the transit trade from Afghanistan and Central Asia would continue through Pakistani ports.

However, Pakistan will have to overcome its internal governance and security challenges to benefit from what is appearing to be a new, more favourable geopolitical environment.