The Diplomat King: The Shah’s Foreign Policy

Published on: 2020-08-03

By: FARAMARZ DAVAR – Monday, 27 July 2020

Forty years have passed since the death of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, the last king of Iran. Despite serious flaws in the domestic politics of the last Shah of Iran, his performance in foreign policy indicates a deep understanding of international diplomacy and Iran’s ability to be a significant actor on the world stage.

Mohammad Reza Pahlavi played an important role in the establishment of OPEC, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, and the Organization of the Islamic Conference, later renamed Islamic Cooperation. He was an active participant in the founding of the United Nations, the formation and Iran’s membership in the CENTO Pact. He also worked to resolve of age-old border disputes with Iraq, including the issue of navigation of the border river, and fostered coexistence between Iran and Iraq. Other key parts of the Shah’s work to regulate foreign relations included the liberation of Azerbaijan from Soviet occupation, the re-establishment of Iran’s sovereignty over the three Persian Gulf islands in exchange for accepting Bahrain’s independence, arranging military aid to Oman and Sultan Qaboos to confront the Dhofar rebels, resisting the establishment of Israel and supporting Saudi Arabia.

He became king of Iran at a time when parts of the country were still under effective Soviet control, in the northern, and British occupation in the south. At a conference of Soviet, American, and British leaders in Tehran at the end of the Second World War, the Shah learned of the presence of Joseph Stalin, Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill after their arrival. Contrary to the political and ceremonial hierarchy at the time, the Shah personally visited Churchill at the British Embassy.

Despite the shaky geopolitical situation, less than two decades later, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s position as head of state and Iran’s situation more generally had stabilized to the point where he was able to set the conditions for relations with the most powerful Western countries at the time: the United States, Britain and France. This period in the history of Iran is known as the era of “independent national policy”.

Ardeshir Zahedi, Iran’s foreign minister from 1966 to 1971, says: “In the last years of the monarchy, Iran no longer had a dispute with any country. His [the Shah’s] policy was respected and everyone knew that he was driven by the interests of Iran and not by the demands and expectations of other countries.”

Iran’s good relations with other countries the world over had made the Iranian passport a token of national pride. Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, one of the most influential figures in the establishment of the Islamic Republic and himself an opponent of the Shah, said 35 years after the revolution: “I drove around all the European countries myself. When I wanted to go from one country to the next, I just showed my passport. Today we have reached a point where people are afraid to take their wives abroad because it [their reception] will be disrespectful.”

Once Assertive in Relations With the West, Iran Now Has an Empty Hand

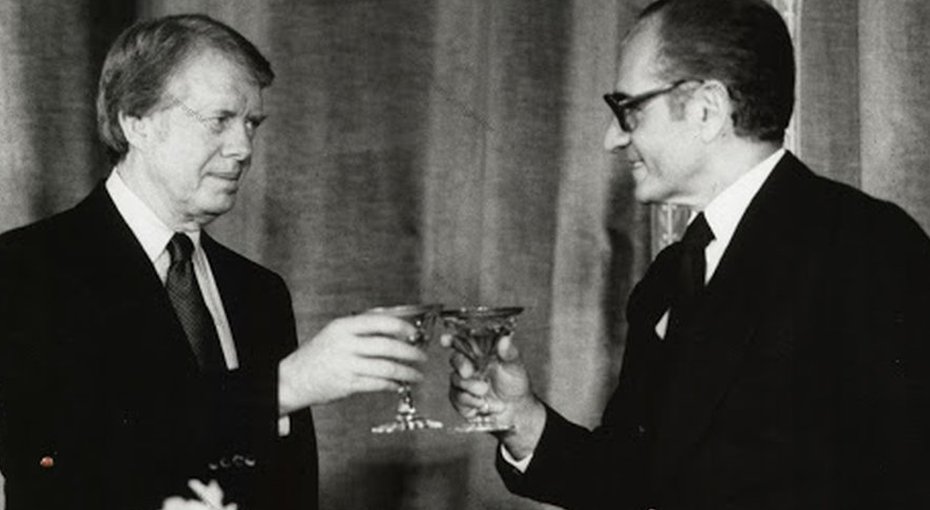

Maintaining very close relations with the West was one of the emblematic features of the reign of Mohammad Reza Shah. Extensive relations with the United States in the economic, political, military and cultural fields, despite 40 of severance, have not yet been fully resolved and their effects are still tangible. The closeness between Iran and Western European countries such as Britain, France, and West Germany was such that Iran owned a French uranium enrichment plant, bought heavy weapons from Britain including a consignment of Chieftain tanks, while Germany was building a nuclear power plant in Iran.

By comparison, today, the toughest sanctions in the history of the United States against a foreign country are now imposed on Iran. The two countries have come to the brink of war several times in the last 40 years, and once participated in a major military conflict in the Persian Gulf. Sensitive technical and military cooperation with Iran is sanctioned by the European Union. The Chieftain tanks the Islamic Republic bought from Britain never arrived, and Britain has not paid Iran back for these due to ongoing sanctions. France and Germany, which were partners in Iran’s nuclear program during the Shah’s reign, were among the countries to express dire concern about the Islamic Republic’s nuclear program in the years after the 1979 Islamic Revolution.

Brilliant relations between Iran and the West during the last 20 years of the Shah’s reign did not mean that Iran fell into the hands of the West or had its political independence violated: a common refrain repeated by supporters of the Islamic Republic. The situation from the 1950s onwards was different, and the country’s heads of state felt able to be assertive in their negotiations with foreign delegates.

“One day,” Zahedi recalls, “British Ambassador Sir Dennis Wright had a meeting with me and he was late. The appointment was canceled and he returned to the embassy. I ordered them not to give him an appointment for three weeks.

“A few years earlier, the US ambassador had also visited Foreign Minister Anoushirvan Sepahbodi without prior appointment. When he found that he was not at the ministry building, he had asked the Shah to reprimand him. That situation had changed now.”

From Friend to All to ‘Neither East Nor West’

Iran’s relations with China and the Soviet Union were also both warm and authoritative. In 1968, during the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, Iran unexpectedly criticized the Soviet Union and sympathized with Czechoslovakia. Shortly after the attack, the Shah was scheduled to pay an official visit to Moscow.

The then-Iranian foreign minister believed the Shah should cancel the trip in protest against the occupation of Czechoslovakia – or postpone it until some unspecified point in the future. “The Soviets fell into disarray,” says Zahedi, “because it was too expensive for them in terms of prestige. Eventually, it was decided to make the trip.

“When they wanted to draw up a joint declaration in Moscow, Soviet officials came and said that His Majesty had agreed to mention Czechoslovakia in such a way that showed that Iran would understand the Soviet’s position. I said yes, that’s absolutely right. I was told to state in a joint declaration that we considered the entry of Soviet tanks into Prague a clear violation of Czechoslovak sovereignty and condemned it in accordance with international rules. You can also mention your own position…

“At lunch, the Soviet foreign minister Andre Gromyko told me, ‘I agree with you. It is not necessary to mention anything outside the relations between the two countries in the declaration.’ You see, Iran had an opinion: a position that opposed to one of the two superpowers of the world at that time, on a very sensitive and important issue.”

Relations between Iran and the People’s Republic of China were also established at the end of the Shah’s reign. One noteworthy historical point is that back then, Iran had such a sturdy international reputation that it played a role in the resumption of US-China relations. The third volume of Ardeshir Zahedi’s memoirs relays this period in detail.

After the fall of the Shah and the rise of the Islamic Republic, the situation changed rapidly. The Shah’s performance in foreign relations, which had been that of “Friend to all and enemy of none”, quickly gave way to the policy of “neither East, nor West”: a policy which apparently does not leave room for friendship or tolerance.

Iran, once called the heart of the Middle East at a time when the Middle East was called the heart of the world, has been so turbulent in its foreign relations and so mired in war and sanctions and conflicts that even 41 years after the establishment of the Islamic Republic, its citizens have not known a single month without incident. The situation has changed beyond recognition – and it seems there is little appetite for change on the part of the regime. Four decades after the Shah’s death, the Islamic Republic’s Foreign Minister, Mohammad Javad Zarif, said: “We chose to live this way.”