How Edinburgh became the Aids capital of Europe

Published on: 2019-12-01

Image copyright

Image copyright

BBC/Two Rivers

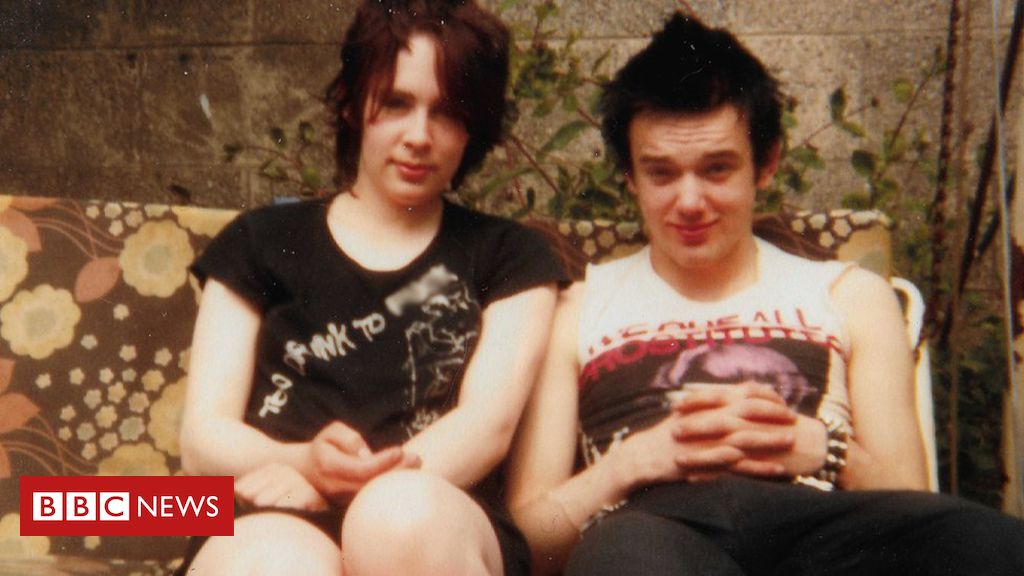

Fiona Gilbertson with her boyfriend, Raymond, in the 1980s. They were both heroin users. Raymond later died of Aids

In the mid-1980s Edinburgh became known as the Aids capital of Europe. A new deadly disease, cheap heroin and the hardline attitudes of the authorities were the ingredients for a public health disaster.

The disease had first surfaced in the US where it became stigmatised as the gay “plague” because it was mainly affecting homosexual men.

But in Edinburgh it was a different group whose health was causing concern – a new generation of intravenous drug users.

Heroin had hit Scotland’s capital hard and fast in the early 1980s, with the number of addicts rocketing from a few dozen to thousands.

New cheap supplies of the drug from Afghanistan and Iran led to a massive increase in injecting drug use, especially on Edinburgh’s housing schemes such as Muirhouse and Pilton.

While Glasgow had more users, it was Edinburgh where the Aids epidemic hit hardest.

And Dr Roy Robertson, a GP on the sprawling Muirhouse estate, was among the first doctors to work out why.

Image copyright

BBC/Two Rivers

Dr Roy Robertson worked as a GP on Edinburgh’s Muirhouse estate during the 1980s and spent his days dealing with an escalating heroin problem.

He made the connection between addicts’ habit of sharing needles and the city’s spiralling Aids crisis.

When the test for the HIV virus was developed in late 1985 he went back and tested blood samples that had been taken from drug users a couple of years earlier when there was an outbreak of hepatitis B.

Retrospectively testing blood samples without permission is something that might now be considered unethical but at the time it led to a breakthrough.

His research, published in 1986, found 51% of the 164 heroin users tested were positive with the virus that caused Aids.

And these blood samples were two or three years old so in reality the problem could be much worse, with an estimated 85% being infected.

“That was an epidemic,” Dr Robertson tells the documentary Choose life: Edinburgh’s battle against Aids. “In no other city in the UK was there an epidemic.”

Dr Robertson says: “We didn’t know how awful this was going to be. We didn’t know all these people would go on to develop Aids if they had no treatment.”

The GP said there were hundreds of drug addicts on his estate because heroin was being sold on the streets for just £5 a packet. But once they had an addiction, it was costing £50 or more a day to feed their habit.

This led to a huge increase in crime and Lothian and Borders Police cracked down hard.

Image copyright

BBC/Two Rivers

Heather Black lived in Muirhouse in the 1980s

Drugs counsellor Rowdy Yates says police activity in Edinburgh in the early 1980s was “ruthless”.

Former police chief Tom Wood admits they were trying to use traditional law enforcement efforts to tackle a social phenomena and they “could not hope to succeed”.

Their attempt to eradicate drugs by force proved to be counter-productive.

One of the impacts of the police’s war on drugs was a crackdown on hypodermic needles used to inject drugs, forcing the city’s addicts to share.

Image copyright

BBC/Two Rivers

Fiona Gilbertson with her boyfriend, Raymond, in the 1980s

“I don’t think I ever used a clean needle,” says Fiona Gilbertson, who lived on the Muirhouse estate and first took heroin in a friend’s flat when she was 17.

“It was almost sociable and we all used the same needle,” she says. “It was just normal to be using dirty needles. It was normal to sharpen them on a matchbox.”

She says the same needle was used for months by the 10 or 20 people in the “shooting galleries” of the rundown estate’s flats.

“At one point there was nowhere in Edinburgh you could get a clean needle,” says Ramsay Prior, a former addict and dealer.

He says people were stealing used needles from the infirmary.

Image copyright

BBC/Two Rivers

Dr Brettle spent three decades working in Edinburgh to combat HIV infection

Health experts began calling for free clean needles and syringes to be provided to the addicts to better contain the disease.

But Dr Ray Brettle, who had become interested in Aids while in the US, says he was met with “ambivalence” when he came back to Edinburgh.

“People did not think this was going to be a big issue,” he says. “For two years most people thought I was being a bit over the top about the whole thing.”

Dr Brettle went on to become head of the infectious diseases unit at Edinburgh’s City Hospital.

When the risks of the virus were finally identified and understood, a major concern became HIV spreading into the heterosexual population at large through prostitution.

June Thomson tells the documentary about her friend Donna who got into prostitution to make money to feed her habit.

“These men, knowing that HIV was starting to be such a big thing, would pay her extra to not use a condom,” she says. “And worse than that she would do it for the extra money.”

Image copyright

BBC/Two Rivers

Princess Diana was a very public supporter of AIDS charities and in the late 1980s. She is seen in this photograph talking to Derek OGG, QC, co-founder of Scottish Aids Monitor (SAM)

By April 1987, the UK government’s policy had shifted and Edinburgh opened its first needle exchange.

Despite the change in policy, the police still found it hard to accept that addicts could just turn up to get clean needles.

“For the first while there were uniform cops hanging outside the needle exchange seeing who came. Maybe having warrants for arrest of some people,” says Tom Wood.

Looking back, Dr Robertson, who has since become professor of addiction medicine at the University of Edinburgh, says the “hostility” towards drug users and the lack of medical intervention created conditions that were ripe for the spread of the virus.

Police officers now admit they were antagonistic towards Dr Robertson because he seemed to be advocating drug abuse.

“Policing is a supertanker,” says Mr Wood. “It takes a long while to turn. The whole world changed in 10 years and policing changed completely.”

In 1987 the first anti-retroviral drug was approved, providing short-term survival for those with Aids.

Further advances have led to more successful long-term treatments.

But now health authorities are dealing with the UK’s biggest HIV outbreak in 30 years. This time in Glasgow.

Choose life: Edinburgh’s battle against Aids is on BBC One Scotland at 21:00 on Thursday 5 December.