MADRID — Pablo Iglesias and his Podemos party burst onto the Spanish political scene in 2015 by winning more than one-fifth of the vote in their first national election, igniting dreams of overtaking the Socialists as the largest left-wing party and reshaping the government.

Instead, after his meteoric rise, Mr. Iglesias faced internal party tensions and endured the same kind of criticism of his leadership and lifestyle that he had long thrown at a political establishment he called “the caste.” Support for his party has fallen sharply.

Yet Mr. Iglesias, 41, now looks likely to get his first chance to at least share power, under a deal that would see him take the post of deputy prime minister and his party become the junior partner in a government headed by the more moderate Socialist leader, Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez.

With sharp rivalries and policy differences, it is an uneasy alliance, and the road ahead for Mr. Iglesias could be every bit as rocky as the last few years have been. But if Mr. Sánchez can win parliamentary approval for his proposed coalition, it would make Spain one of the few European countries — and easily the largest — where far-left ministers form part of government.

Podemos arrived in Parliament riding a wave of mass protests against austerity cuts brought about by the debt crisis that battered much of Europe. In its first national campaign, Podemos became the most successful third party since Spain returned to democracy in the 1970s. Another newcomer, Ciudadanos, placed fourth.

Mr. Iglesias dismissed the traditional major parties as an entrenched, unresponsive and out-of-touch establishment. Podemos took as its model another far-left, anti-establishment party — Syriza — which surged to power in Greece in 2015 on an anti-austerity platform, and governed until it was ousted in elections this year.

But once in Parliament, the pony-tailed Mr. Iglesias found it harder to cast himself as a critical outsider. He got entangled in unsuccessful negotiations on forming a government, and lost support even after merging Podemos with a smaller left-wing party.

On Nov. 10, the rebranded Unidas Podemos party won just 35 of the 350 seats in the lower house of Parliament — half as many as it had taken in the 2015 and 2016 elections. It finished fourth, behind a far-right newcomer, Vox.

Santiago Abascal, the leader of Vox, has led right-wing attacks against Mr. Sánchez, accusing him of “embracing Bolivarian Communism” — equating him with Hugo Chávez, the Venezuelan leader who died in 2013 — by allowing Mr. Iglesias into his government.

Mr. Sánchez and Mr. Iglesias signed their pact only two days after the Nov. 10 election, embracing for the cameras — a contrast to the acrimony that marked their previous months of fruitless negotiations, which had forced Spain into its fourth election in four years.

But even combined, the two parties are short of a majority. And so, having come to terms with Mr. Iglesias, Mr. Sánchez must still win support from some smaller parties, probably including Catalan separatists, to allow him to form a new government.

His next challenge would then be to keep together his minority coalition government amid a European economic slowdown.

If there were a recession, “Podemos could have every interest in showing a differentiating factor, to convince the electorate that whatever frustration builds up should not be attributable to them,” said Ignacio Jurado, a politics professor at Carlos III University in Madrid.

The media-savvy Mr. Iglesias, who appeared regularly on television chat shows before entering politics, has sought to recast himself as a statesman rather than as a firebrand. During a televised campaign debate, he repeatedly read out articles from Spain’s Constitution, while reminding other candidates to respect the country’s laws.

Before founding Podemos, he and some of his allies taught politics at universities and worked as political consultants in Latin America, including for the government of Mr. Chávez. Once the party gained traction, they faced news reports that Podemos had received undeclared money from Venezuela and Iran, a claim they have repeatedly denied.

Mr. Iglesias argues that under the conservative government that lost power last year, his party long suffered from a state-backed media smear campaign, orchestrated by a high-ranking former police official, José Manuel Villarejo.

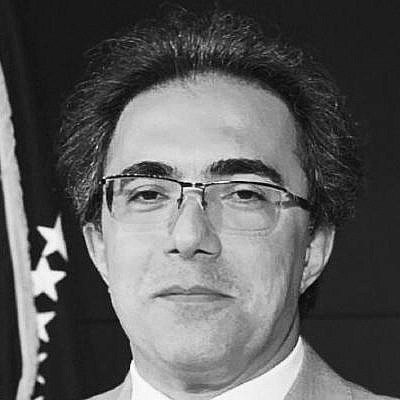

Image

Mr. Villarejo is in jail, awaiting trial on charges of bribery and money laundering. Prosecutors say he grew rich while working for years as a secret fixer for political and corporate clients, spying on and smearing their enemies, and even fabricating evidence. Conversations he secretly recorded have leaked, casting an unflattering light on Spain’s wealthy and powerful.

Unidas Podemos contends that Mr. Villarejo was behind false claims about the party’s foreign financing, and that he eavesdropped illegally on party officials. Mr. Iglesias is a party to one of several court cases centering on Mr. Villarejo.

“We can perhaps understand, without ever justifying, that a state uses illegal mechanisms to fight terrorists, but not to fight a political formation,” Mr. Iglesias said during a recent meeting with a group of foreign journalists.

But even if the legal tangle around Mr. Villarejo vindicates Mr. Iglesias and Unidas Podemos, their problems will be far from solved.

Polarization in Spain has deepened recently, with Vox finding a receptive audience for its anti-immigration and ultranationalist rhetoric, and political power is more fragmented than ever.

Mr. Iglesias has fallen out with some of his closest colleagues, and last year, he beat back an attempt to topple him as party leader. That challenge followed claims that he and his partner and fellow politician, Irene Montero, had violated the working-class principles of Unidas Podemos by buying a villa in Spain’s wealthiest municipality, outside Madrid.

This year, Íñigo Errejón, a co-founder of Podemos, broke away and formed his own party to contest the recent elections, though it won only three seats.

Once in government, Mr. Iglesias and his party may find working with the Socialists, who have a more cautious agenda, a frustrating experience. Unidas Podemos wants higher taxes on corporations and the rich, an increased minimum wage, a 34-hour workweek and caps on property rental prices. The party also wants banks to reimburse the government for the bailout money they received during Spain’s 2012 financial crisis, while keeping Bankia, the largest rescued lender, under state control.

The Socialists have advocated more modest tax increases, and have not talked about squeezing the banks. They sharply increased Spain’s minimum wage this year, and have shown no interest in raising it again any time soon.

But the main sticking point could be that Mr. Iglesias has argued that an independence referendum in Catalonia — with terms set by Madrid — could help end Spain’s simmering territorial conflict. Two years ago, the regional government held a referendum that the central government and the courts called illegal, plunging Catalonia into chaos.

Before the election last month, Mr. Sánchez promised not another independence vote, but a stronger clampdown on Catalan separatists after several nights of violence on the streets of Barcelona and other cities.

When Mr. Sánchez and Mr. Iglesias signed their pact, the Spanish stock market fell.

Former prime ministers from the right and left had urged Mr. Sánchez to form a coalition with a party to his right, not one to his left.

But as long as Mr. Sánchez keeps Socialist ministers, and not those from Unidas Podemos, in charge of the economy, it seems unlikely that his coalition will cause major concerns among Spain’s European Union partners.

“I think the European Union prefers a government with Podemos rather than more deadlock,” said Mr. Jurado, the politics professor. “If the European economy continues to slow down, it’s important to have at least somebody in charge and able to intervene in Spain.”