Khamenei loyalists may tighten grip at Iran elections

Published on: 2020-02-17

DUBAI (Reuters) – Hardliners are set to tighten control of Iran this week in a parliamentary election stacked in their favour, as the leadership closes ranks in a deepening confrontation with Washington.

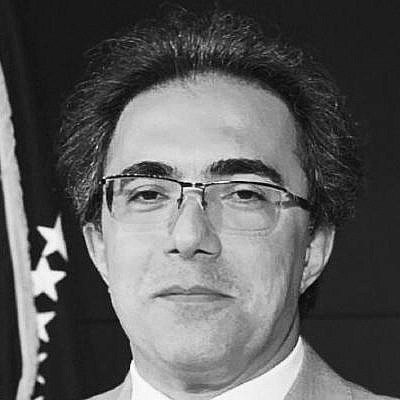

FILE PHOTO: Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei speaks live on television after casting his ballot in the Iranian presidential election in Tehran June 12, 2009. REUTERS/Caren Firouz/File Photo/File Photo

Big gains by security hawks would confirm the political demise of the country’s pragmatist politicians, weakened by Washington’s decision to quit a 2015 nuclear deal and reimpose sanctions in a move that stifled rapprochement with the West.

More hardliner seats in the Feb. 21 vote may also hand them another prize — more leeway to campaign for the 2021 contest for president, a job with wide day-to-day control of government.

Such wide command of the power apparatus would open an era in which the elite Revolutionary Guards, already omnipresent in the life of the nation, hold ever greater sway in political, social and economic affairs.

Allies of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei have ensured hardliners dominate the field, removing moderates and leading conservatives and permitting voters a choice mostly between hardline and low-key conservative candidates loyal to him.

“Literally, it is not a race anymore. Hardliners want the presidency. This is the end of moderation for at least a decade if not more,” said an official on condition of anonymity.

Like hardliners, conservatives back the ruling theocracy, but unlike them support more engagement with the outside world.

Faced with little choice, many voters are likely to be focused on bread-and-butter issues, in an economy hurt by U.S. President Donald Trump’s “maximum pressure” policy towards Iran.

With Iran facing growing isolation and threats of conflict over its nuclear standoff with the United States, and growing discontent at home, the turnout is seen as a referendum on the establishment — a potential risk for the authorities.

REVOLUTIONARY GUARDS POWER

Many Iranians are furious over the handling of November protests against fuel price hikes which swiftly turned political with demonstrators calling for “regime change”, leading to the bloodiest unrest in the history of the Islamic Republic.

A crackdown overseen by the Revolutionary Guards killed hundreds and led to the arrest of thousands, according to human rights organisations.

The public is also livid over the accidental shooting down of a Ukrainian passenger plane in January that killed all 176 people on board, mainly Iranians. After days of denials, Tehran admitted that the Guards were to blame.

But Khamenei’s loyalist candidates are backed by core supporters of the establishment who identify in all aspects of life with the Islamic Republic, insiders said.

“Their supporters believe in the establishment and they will vote because they see it as a religious duty. Hardliners will benefit from a low turnout,” said the government official.

Speaking to Reuters, some authorities predicted a turnout of about 60% for the 290-seat assembly, compared to 62% and 66% respectively in the 2016 and 2012 votes. Some 58 million Iranians out of 83 million are eligible to vote.

“Iran is not only Tehran or other major cities where voters are politically motivated. In small cities, towns and generally in rural areas people will vote,” a hardline official said.

With no independent, reliable opinion polls in Iran it is hard to gauge which way the ballot will go, let alone the extent to which Khamenei and the Guards will exert their influence over the vote to cement their grip on power.

But pro-reform voters are dismayed by disarray in their camp and the failure of pragmatist President Hassan Rouhani to abide by an election pledge to ease social and political restrictions.

“Many Iranians (who voted for Rouhani) have lost their hope for reforms,” said a reformist former official. “They don’t trust the reform movement anymore. They want change and only change.”

A hardline dominated parliament could mount pressure on Rouhani, architect of the nuclear pact, who has been criticised by Khamenei’s influential allies for his performance in power.

“I beg you not to be passive … I am asking you … not to turn your back on ballot boxes,” Rouhani said in a speech on Feb. 11.

The slate of hardline candidates is dominated by the Guards, who answer directly to Khamenei, and their affiliated Basij militia, insiders and analysts say.

Aside from its vast economic holdings, the Guards have grown more politically assertive in recent decades, with increasing numbers of veterans in legislative and executive powers.

Former Guards commander Mohammad Baqer Qalibaf, who according to a leaked U.S. diplomatic cable from 2008 has benefited from strong support from Khamenei’s son Mojtaba, tops the parliamentary lists of main hardline groups in Tehran.

BALANCE OF POWER

“We will serve wherever the revolution and our Imam (Khamenei) need us,” said a former Guardsman, who served in the government of former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. His re-election in 2009 sparked protests for months against alleged vote-rigging.

Parliamentary elections have scant impact on Iran’s foreign or nuclear policies, which are set by Khamenei, and major pro-reform parties have been either banned or dismantled since 2009.

But the vote shows shifts in the factional balance of power in Iran’s unique dual system of clerical and republican rule.

Mass disqualifications of candidates in 2004 parliamentary polls sidelined reformists for years. It ushered in hardline Ahmadinejad in 2005.

In 2016 voters handed gains to centrists and moderates, suggesting many sought more open democracy and wider freedoms.

This time, the Guardian Council, a hardline vetting body, has disqualified 6,850 hopefuls out of 14,000, ranging from moderates to conservatives, from contesting parliament polls. About a third of sitting lawmakers have also been barred.

“We did what we were supposed to do, now it is your (voters) turn,” said head of the Council Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati.

Several politicians including Rouhani strongly criticised the Council’s rejection of over 50% of hopefuls. The watchdog denied any bias.

Khamenei, who has the final say in Iran’s complex ruling system, has backed the watchdog, saying parliament has no place for “those scared of speaking out against foreign enemies”.

Writing by Parisa Hafezi, Editing by William Maclean