House Speaker Nancy Pelosi was essentially forced into impeachment. Now, after a little less than two months of investigation, she hopes to bring the process to a close. On Tuesday, House Democrats revealed their articles of impeachment against the president. One focuses on abuse of power, the other on obstruction of Congress.

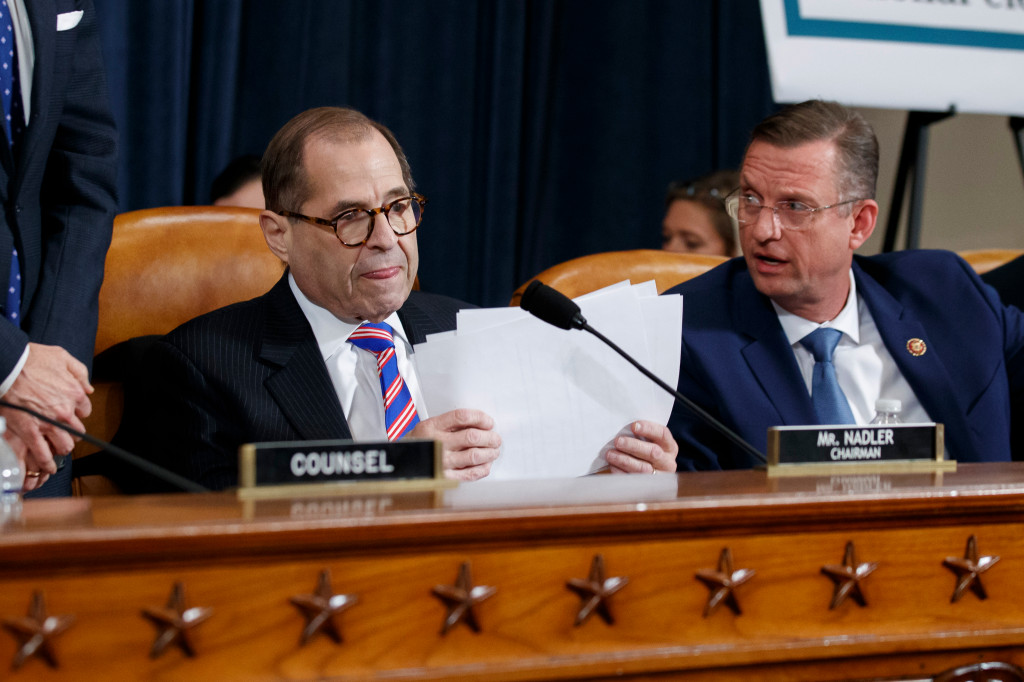

“Our president holds the ultimate public trust,” Representative Jerrold Nadler, the chairman of the House Judiciary Committee, said. “When he betrays that trust and puts himself before country, he endangers the Constitution, he endangers our democracy and he endangers national security.”

Pelosi promised a narrow, expedited impeachment, and that’s what the House will deliver: a targeted effort centered on a single act of malfeasance. It’s been a fast-paced process meant to satisfy liberal activists without alienating moderate members worried about support from swing voters. Once it’s completed, Pelosi can say that Democrats ran a sober investigation and found definitive evidence of wrongdoing. She can even say that this wasn’t an obstacle to getting things done — it was hardly an accident that after announcing the articles of impeachment, Pelosi also announced that the House would vote to approve the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, President Trump’s renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement.

Pelosi wants to get to the bottom of the president’s wrongdoing and she wants to protect her moderate members. But a quick, narrow impeachment isn’t the way to go. On the substance, there’s still a lot to learn about the president’s behaviors, hints of corruption and illegality that should be pursued. And on the politics, the fate of the House majority — and the fate of the eventual Democratic nominee’s presidential campaign — rests more on the national political environment than the particulars of each swing congressional district. Individual Democrats might have run on health care in 2018 and other “kitchen table” issues, but it was anti-Trump energy that put these districts within reach, and it will be anti-Trump energy that drives the outcome next year. If the president is unpopular — if he’s mired in controversy — Democrats will likely win. If it’s the reverse, if Trump can overcome scandal and recover ground with some voters, he’ll win re-election. And those vulnerable House Democrats? They’ll lose, along with the party’s nominee.

The quick impeachment has another, critical weakness: It hands the process to the Republican Senate and its majority leader, Mitch McConnell. Even if Senate Republicans decline to call witnesses, they still have an opportunity to use the proceedings to try to inflict political damage on Democrats. President Trump, for example, wants the Senate to litigate his anti-Biden conspiracy mongering.

The better alternative — the stronger alternative — is to wait. Pursue new investigations to support additional articles of impeachment. Expand them beyond Ukraine: Investigate corruption and wrongdoing throughout the administration and accomplish as much as you can before handing the process over to the Senate.

On Ukraine, for example, Democrats could pursue testimony from figures who appear to have direct knowledge of the extortion scheme, including the president’s lawyer, Rudy Giuliani, his former national security adviser John Bolton and his secretary of state Mike Pompeo.

Democrats should also pursue other violations, like the president’s open attempt to enrich himself through the presidency. This summer, for example, Trump tried to steer next year’s G7 meeting to his luxury golf resort in Doral, Fla., a blatant attempt to profit from the Oval Office. And last week we learned that Trump all but steered a $400 million contract for border wall construction to a North Dakota-based company, Fisher Sand and Gravel, whose chief executive, Tommy Fisher, has been a staunch defender of the president on Fox News. If the Ukraine scheme was an attempt to corrupt our foreign policy to help his re-election, then both incidents represent an attempt to corrupt the presidency for personal gain. This, too, demands investigation and public scrutiny.

Then there are the call transcripts. In his complaint, the whistle-blower who set off the Ukraine investigation accused White House officials of hiding the transcripts of politically sensitive calls with foreign leaders in the same restricted computer system that is used for highly classified information. It’s possible that the Ukraine conversation is part of a pattern of similar behavior.

To that point, Democrats could investigate the relationship between Trump and the president of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdogan. We know Trump’s sudden decision to abandon America’s Kurdish allies in Syria stemmed from an “off-script moment” during a phone call between the two. We know that a gold trader connected to Giuliani was charged in a scheme with a Turkish bank to evade American sanctions on Iran. And we also know Trump has personal business interests in Turkey. Absent investigation, there’s no way to know if any of this influenced the president’s decision-making on Syria. But if it did, it, too, would constitute another impeachable offense. There’s a similar case for investigating the president’s highly solicitous relationship with Saudi Arabia, which is so unusual that his response to the shooting of American service members by a Saudi national on American soil was to promise compensation from the Saudi royal family and otherwise dismiss the situation, acting more like the press secretary for the kingdom than the president of the United States.

If Democrats aren’t compelled by the reality of broad, pervasive corruption, then they should be compelled by the politics of a longer, more deliberate impeachment process. The White House and its Republican allies have struggled to address the Ukraine investigation. The president’s approval hasn’t fallen, but it also hasn’t grown, despite the strong economy. Impeachment has consumed Trump’s energy and put him on the defensive. It’s done the same to Republicans, forcing them to explain and account for his behavior. It’s mired the entire party in scandal, with no apparent cost to Democrats — the party just won a governing trifecta in Virginia, held the governor’s mansion in Louisiana and beat an incumbent Republican governor in Kentucky.

There’s no reason for Democrats to end things now. They have enough material to keep the pressure through the new year. They can show the country what Trump has done with his power, and why he shouldn’t be allowed to wield it any longer. Close scrutiny will also discourage the president from new attempts to leverage his office for personal gain, and if nothing else, an extended impeachment process will keep the process away from Mitch McConnell.

Democrats, in other words, can use the power of impeachment to set the terms of the next election — to shape the national political landscape in their favor. In a political culture governed by negative partisanship and hyperpolarization, restraint won’t save the Democratic majority. But a relentless anti-Trump posture — including comprehensive investigations and additional articles of impeachment — might just do the trick.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram.